Beirut, 1970. In an office of the People’s Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), writer Ghassan Kanafani is interviewed by Australian journalist Richard Carleton. During the conversation, the journalist asks Kanafani precisely the question that the Western world has insisted on asking Israeli and Palestinian leaders for around 70 years: why not sit down and talk?

When asked, Kanafani, a man with a dark face, a dense mustache and penetrating eyes, firmly replies: “Talk to who…?!” “About what?!” In the video, it is not possible to see Carleton’s reaction, but his surprise is almost palpable. Once the shock is over, the journalist replies: “just talk.” With the Israelis, of course.

In the fragment cited above, a certain Western tone in what the journalist says is clear, but also a look, a very particular way of analyzing the conflict that is deeply marked by illuminate rationality: “If there is a conflict, there must be a rational solution for it.” What this false premise can hide is, precisely, the need for a correlation of forces that makes the talk possible. A talk between militants and the president of a state? Between a cutting-edge army with the support of the greatest military power in the world and some guerrillas? Quickly, Kanafani concludes his reasoning with the following sentence: it would be “a talk caught between the devil and the deep blue sea!”

As Kanafani insisted in that interview, answering those questions—“talk with whom?” “About what?”—is essential to establish the parameters of any understanding of the Israel-Palestine relations. And that is the central theme of the analysis that I propose in this text. The date I write it (May 15) is emblematic. On a day like today, in 1948, the British Empire left Palestine and the State of Israel was thus founded, fulfilling a decision of the United Nations (UN), dated 1947. As a consequence, between 1947 and 1949, various massacres resulted in the expulsion of more than 750,000 people from their country of origin, without the right to return. We’re speaking of almost half of the local population. For this reason, for Palestinians around the world, May 15 is the date on which the Nakba (catastrophe/disaster) is remembered.

Thinking of the lessons given by the Palestinian cause, another May 15, this time in 2020, I defended my Ph.D. thesis “Resistance Time: An Atlas of Conflicted Temporalities.” My main argument was that the iconography produced by Palestinian culture in the last 70 years suggests a kind of sui generis temporality: the time of resistance. In other words, I defended in my thesis the idea that, unlike the frenzy for progress and the state of permanent investment of resources in a future time, which define Western culture, time in Palestinian visual works (cinema, posters, graffiti), seemed to suggest a present charged with the past, in which a particular way of resisting extends from the Nakba to the present day, in 2021. What that visuality reflects is precisely a kind of extended temporality where the only marker that exists is the reference to the past and the struggle for existence in the present. It is, therefore, a time of resistance.

In such a temporary zig-zag, I return to May 15, 2021. After an event that occurred on the first day of that month (05/1), Palestine was once again a topic in the international media. Interestingly, this story also begins with a conflict over territory. In a house located in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood of East Jerusalem, a 22-year-old Palestinian woman and a Jewish settler argue. During the confrontation, a fragment draws attention in the dialogue:

“Yakub, you know this is not your house,” says Palestinian Muna Al-Kurd.

Across the courtyard, the settler Yakub, a white man, wearing glasses, a kippah and with a long blond beard, replies:

“Yes, but if I go, you don’t go back, so why are you yelling at me?”

Next, Muna, insists almost patiently:

“You are stealing my house.”

The conversation took place on Saturday (05/1) and was recorded on the cell phone of activist Tamer Maqalda. Days later (05/8), the video had been published on Tamer’s Instagram profile and went viral on digital media. More than an emblematic event, or a smaller-scale representation of the Nakba, the dialogue between Jacob and Mona is evidence of a process of repeated violence. In other words, the fact that Mona has tried to defend her own home, and that Jacob has admitted that he is stealing it, is precisely the continuity of a colonial process that began in 1948 and was aggravated by the illegal expansion of the State of Israel, after the Six-Day War in 1967.

The scene also represents an even more specific process, related to Palestinian families who have resided in Sheikh Jarrah for decades, after having been expelled from other regions of Jerusalem by the division of the city produced by the founding of Israel (in 1948). It is, therefore, a second process of expulsion, in this case, of the families.

The terms of the dialogue

A first consequence of the onslaught between Yakub and Muna, which is also the dilemma of other families in Sheikh Jarrah, was the protest of the Palestinians who, unlike the majority, have Israeli citizenship and live in Jerusalem. The protest was followed by tensions between Israeli Jews and Arabs, and groups of Jewish extremists’ persecution of Palestinians.

According to Ramzy Baroud, from the Arab News network, the events had the direct participation of extreme right-wing parties, such as Otzma Yehudit, which defends, among other things, the annexation of the West Bank to Israel; and the Lehava, an openly racist and anti-miscigenated movement. In addition, the Israeli police attacked the Al-Aqsa mosque complex—a holy place for Islamists during Ramadan—shooting rubber bullets and throwing tear gas, in an action that injured hundreds of activists, tourists and worshippers.

More than mere state brutality, the act symbolizes Israel’s invasion and control over the history of Jerusalem. The once “backyard” discussion has now taken on municipal proportions: police, parties, far-right militants protected by discriminatory laws, are articulated in the streets. This becomes evident when we look at the numbers that result from this street “conflict.” According to the local newspaper Hareetz, so far, beyond the fact that both Jewish and Arab citizens of Israel have participated in the riots, more than 100 Arabs (116) have been indicted. No Jewish citizen has been so far (zero). Given these figures, how can one speak of “conflicts,” “war” or even “dialogue”?

Without waiting for any kind of reaction from the Israeli legal system, the armed wing of Hamas, a group located in the Gaza Strip, decided to respond with an attack of more than 200 rockets on Tel Aviv, whose vast majority (90%) was deactivated while in flight by the Israeli anti-aircraft defense, known as the “iron dome.” So far, the Hamas attacks resulted in a tragedy accounting for a total of 10 dead, including two children, in Israel. Undoubtedly an unquestionable offensive that has been described—appropriately—by many as a terrorist act.

For its part, in response to the Hamas attacks, the Israeli air offensive on Gaza caused nearly 200 deaths, including 58 children, as reported by Al Jazeera; a fairly common occurrence in the history of Israeli attacks on Gaza. Unlike Tel Aviv-Yafo, Gaza does not have an “iron dome,” nor an airport, nor a supposed democracy. Gaza, which under the Ottoman Empire came to have railroads, a train station and, recently, an airport, has been reduced to an open-air prison since Israel occupied the territory and isolated it, even from the rest of Palestine.

In fact, even if rockets were launched from Gaza, its citizens cannot leave the strip of land where Israel, Egypt and Hezbollah itself are retaining them. Gaza is even denied humanitarian aid, and we are talking about a territory that suffers from the lack of such basic resources as drinking water, for example. In addition to the above, approaching the border between Gaza and Israel is a death sentence for anyone who tries it, as was demonstrated during the 2018 and 2019 protests, which had among their victims, in addition to children, paramedics and journalist Yaser Murtaja who, according to a Washington Post headline, wore a vest that read “PRESS.”

Last week, under the allegation of striking a building used by Hamas, Israel bombed the Al-Jalaa Tower, the headquarters of Al Jazeera and The Associated Press, located in Gaza City. In the only official statement issued so far, the group [Hamas] denies having used the tower for any of its intelligence operations. Thus, although the dates change and time seems to move, there is still violence against civilians and members of the press in the region.

This is why the dialogue between Muna and Yakub only summarizes the complex relationship that exists between vulnerable individuals, unprotected by the State, such as Muna and other Palestinians, and the State of Israel, sometimes represented by Yakub, others for the legal-military apparatus that also involves institutions such as the Army, the police, the extreme right-wing parties or the Supreme Court.

On the other hand, the group of Jewish organizations that fight, in Israel, for the end of the illegal occupation of their State in Palestine must also be highlighted. In fact, one of these organizations, Breaking the Silence, is made up of former Israeli military personnel who, traumatized by their experience in that occupation, have decided to publicly expose the ins and outs of the process. Among its activities, the NGO deals with offering tours of the historic city of Hebron, in the West Bank, where attacks on Palestinians are constant and particularly violent.

As it is possible to notice in any updated map of the region, the proposal that suggests some kind of equality between the parties is absolutely false, as, incidentally, indicates the Israeli Jewish theorist Illan Pappé in Revisiting 1967: The False Paradigm of Peace, Partition and Parity. The date cited in the title of the work refers to the Six-Day War, in which Arab countries tried to invade Israel to retake Palestinian territory and were defeated in less than a week. As a result, Israel invaded Gaza, previously administered by Egypt, the Sinai Peninsula, the Egyptian border with Gaza, as well as the Golan Hills to the north, and the West Bank, which was then—and still is— occupied by Zionist forces.

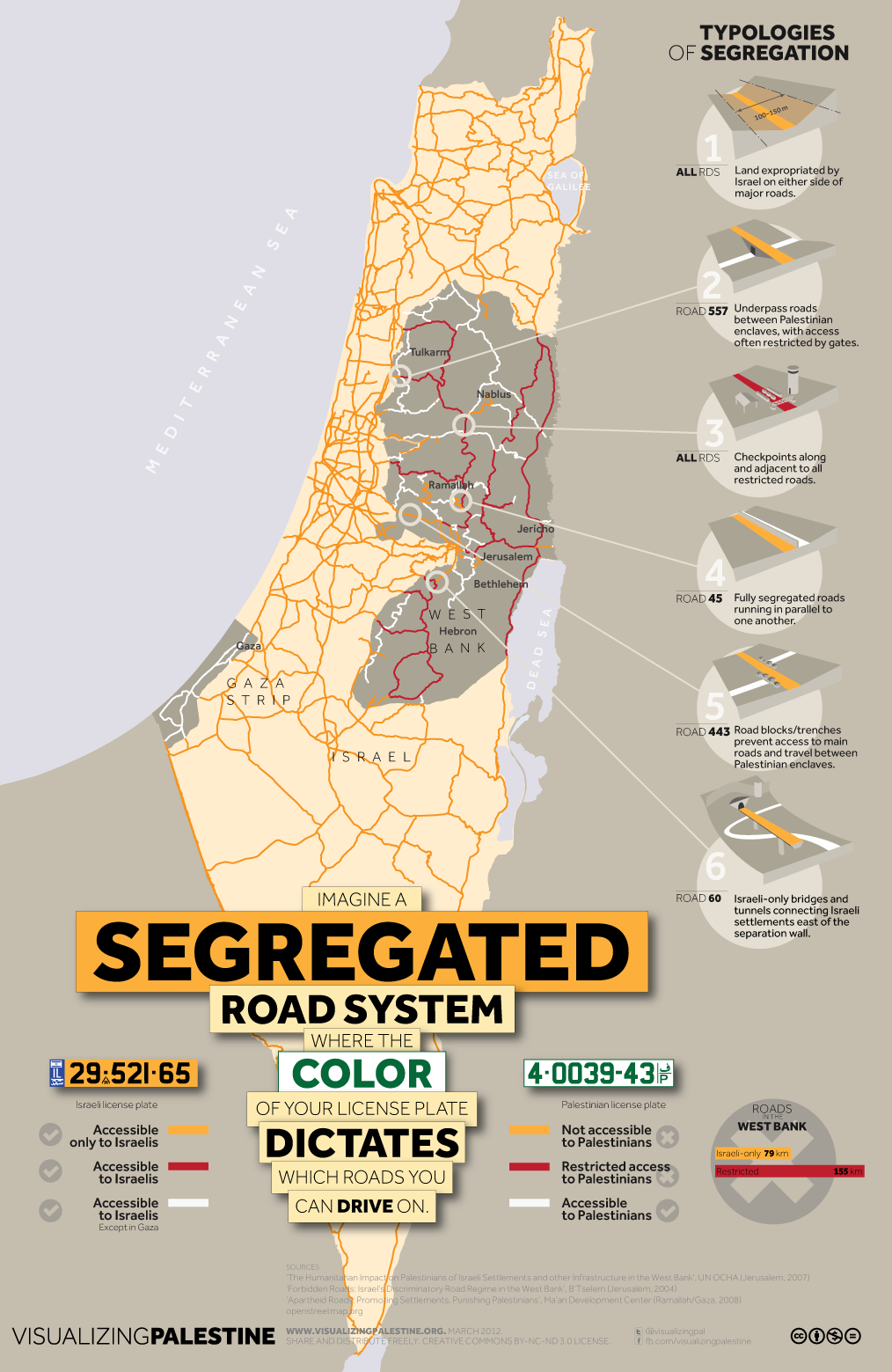

However, to understand this whole panorama of occupation, it is not necessary to go too far; it is enough to know that the West Bank is occupied by Israeli military forces and settlers, in a territorial partition that becomes absolutely clear when the access to roads is observed. These roads, according to architect Eyal Weizman, are part of the architecture of the occupation and, in addition to favoring the flow of Jewish citizens to legally Palestinian territory, they intentionally cross various cities, towns, and arable lands, concentrating the circulation of the Palestinians in that region, as well as the local economy and, above all, sovereignty.

Returning to the confrontation that served as the starting point for this analysis, Yakub’s position, when challenging Muna, illustrates what Professor Hagar Kotef described as colonizing self (The colonizing Self, 2020,) in a book by the same name. For the author, the experience of colonization is constituted precisely based on the operation that transforms violence into “home,” which is perceptible in Yakub’s reaction, who does not go so far as to deny that he is “stealing” and affirms that that is indeed his goal. Yakub’s project is clear: to expel, steal and transform “that place” into “home.” For him, there is no possibility of remorse, because he, Yakub, knows that “if I don’t do it, someone will do it,” which means, in other words, that the State will do it, through other settlers who act as proxies in its name. Yakub is right. He is not to blame for what happens; he is simply an instrument of the true agents in the oppressive structure.

Simply put, Israel’s law operates in an Apartheid regime that has already been denounced by the international organization Human Rights Watch, and by the report “Israeli Practices towards the Palestinian People and the Question of Apartheid,” published by a UN agency, the Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA). According to the authors of the document, Palestinians suffer legal discrimination in four areas. Among the discriminatory reasons and devices cited are civil laws that only restrict the right of Palestinian citizens residing in Israel, residence laws, military laws, and the impossibility of the Palestinians returning to their homeland, whether they are refugees or exiles.

It is no accident that one of the laws that discriminates against Palestinians and acts in favor of Israeli Jews dates back precisely to the year 1970, two years after the end of the Six-Day War. At that time, the aggressive Israeli territorial expansion project became effective, which basically consists of the expulsion of the Palestinians and the acquisition of their lands, thus contrary to various international organizations, such as the UN itself. Back then, Israeli courts began to authorize what they describe as the “repossession of property” to Jewish owners, their heirs, or Jewish associations acting on behalf of the former owners. It is precisely this decision that protects and supports the “legality” in the attempted “theft” that occurred in Sheikh Jarrah, as well as the conversation between Yakub and Muna that unleashed new views on the conflict.

In addition to the aforementioned legislation, which specifically deals with East Jerusalem, the bill includes decisions indicating that Israel may occupy “areas of archaeological interest,” which would justify the expulsion of Palestinians from the West Bank. That is already a reality, for example, in Hebron, where the brutality in the treatment of Palestinians by the Israeli army reaches the point of traumatizing the military themselves.

It is then demonstrated that the onslaught between Yakub and Muna, which occurred in Sheikh Jarrah, is not exactly a novelty, but rather the repetition of a process of expulsion and ethnic “cleansing” that has lasted 70 years. In its most recent configuration, figures such as Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu—Bibi—who had been weakening since the last legislative elections due to corruption scandals, as well as the Israeli extreme right, and Hamas itself—which does not represent the Palestinian people—come out winners.

Overcome by fear, Netanyahu regains some of his weakened prestige at the cost of the recent deaths of civilians in Gaza. With him, the far right is also strengthened without bothering Western powers that buy Israeli drones and weapons that have been tested in/against Gaza for years. By the way, Netanyahu leads one of the best-trained intelligence services in the world, which makes it possible to imagine that he was prepared for the Hamas reaction, which, in addition to being predictable, was convenient for him.

Hamas, for its part, finds in the reported violent events its own condition for existence; after all, its strength is directly linked to the violence and isolation imposed on Gaza. On the other hand, and to complete the terror structure that surrounds Gaza, Egypt continues at this point under a dictatorship that, financed by the United States, maintains the blockade of the region.

An endless conflict?

Faced with these recent events, and almost hampered by the civilizing need to suppress anger and propose a “fair” dialogue, I try to formulate and close this text. The only way I can find to summarize and analyze it is precisely the memory of a trip I made to Palestine in 2019. I especially remember the words of a man with whom I briefly spoke at that time at Checkpoint 300, which connects Bethlehem with Jerusalem.

After a series of constraints, which involved the attempt to go through a metal detector without resorting to the indifferent soldiers who were guarding the premises, and without trays available to place our metal belongings, my traveling colleague, that man, managed to enter with his two children on the bus that would take us to Jerusalem. When he saw me, he approached me still with a thoughtful gait and grabbing the waist of his jeans, and he commented to me that he had forgotten his belt in the midst of the confusion at the checkpoint. Despite that, he seemed to be in a good mood, relieved to have been able to complete his mission. After catching his breath for a few seconds, he grumbled, in Spanish: “Every day is the same. Always the same shit.” The day was coming to an end for him and he would manage to get to his house after that incident, I suppose that is the reason for his joy. I was momentarily relieved for him. His phrase, however, marked me: “Every day.”

The image of that man, surrounded by his children and speaking Spanish that sounded strange to a non-Spanish-speaking Brazilian like me, as well as his strong Arabic accent, his empathy towards me (a complete stranger), and that phrase, would mark me forever. I had not yet managed to finish my doctoral thesis, but that scene better summed up my research problem than the idea of “resistance time” with which I was left in the end. Resistance present in 1948, in 1967, in 1982, during the intifadas, and so many other dates, in so many other days and years that they are not enough to describe the intensity of the “always” Palestinian.

It is not simply about wars with a beginning and end, nor are they conflicts, it is the repetition of colonial expansion orchestrated by an Apartheid state or condition. A state, by the way, that my traveling companion clearly described when leaving that checkpoint. We could even say that yes, it is a dialogue, but a brutal one, which is caught between the devil and the deep blue sea.