With the computer system to apply for unemployment compensation collapsed in the face of the advance of the COVID-19 pandemic, better known as coronavirus, the Florida state government has created a form for applicants to apply by post, which had initially started being distributed in post offices and government buildings. But with a credible figure of 400,000 unemployed in sight, huge lines have started being seen to get them.

It is estimated that there are between 35,000 and 40,000 unemployed in South Florida, a number that will undoubtedly increase as the pandemic spreads. This Wednesday in Miami-Dade County there were 5,354 coronavirus cases and 49 deaths. Unemployment figures are not exact and circulate through informal channels.

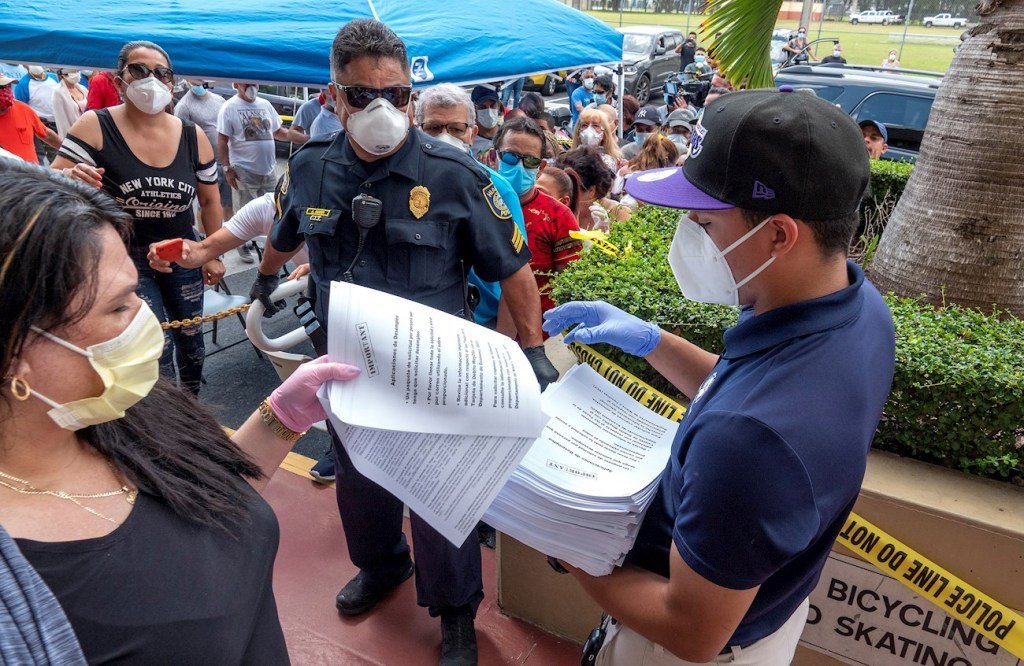

The city hall of Hialeah, a city with a strong concentration of Cubans in the Miami metropolitan area, has set up three locations to serve the public. But the reception has been so large that endless lines were formed that the police had difficulty controlling. “It is very difficult to determine how many have passed through here,” explains the city’s police spokesman, Ibel Pérez. “They have seen that the lines are huge, never seen before except in artistic or sporting events. It is difficult to make an estimate.”

The atmosphere around the John F. Kennedy municipal library is a little hectic. The police try to organize people, although it is not an easy task. Desperate but also undisciplined, Cuban-Americans repeat behaviors that are commonplace on the island. The line is not an example of order. “My mother has explained to me that this is very similar to Cuba,” says one of the police officers trying to put a little order.

The goal is for people to respect the safe distance to lessen the chances of contagion, wear a mask and respect their turn. “Let’s see, ma’am, please go back to the line, keep six feet away from the other person and wear the mask,” says the officer to a woman who has strayed from the line, but without previously warning those who her that she has her turn marked there.

In fact, many, as in Cuba, come to the end and ask: “who’s the last?” And people respond most naturally by saying “it’s me and I’m behind the lady in the blue t-shirt,” after which they move away or sit down on one of the nearby stairs and watch the evolution of the line from a distance. It’s part of the recreation of how the line works, as many have seen and lived since they were born.

The police don’t understand those minor details. Immediately another officer comes by and reminds people of the distance. The large crowd scatters a little, but that doesn’t last long. Far from the police and with some slowness, as if they wanted to go unnoticed, people start to walk slowly, the large crowd restarts and everyone with an innocent face. The officer returns, calls attention and no one is responsible. Some argue with “I got there first, but that one slipped in.” The aforementioned lady says that’s not so and a discussion ensues that is difficult to arbitrate because nobody wants to let their arms be twisted.

Patient, but still with a look of fright on his face, the police officer imposes his authority and makes threats that perhaps border on the illegal. “Follow the rules, if not, I’ll take you out.” Minutes later, the officer would have to admit to OnCuba that the threat is not very legal, but he gives a dogmatic explanation: “Aren’t they treated like this in Cuba? They understand….”

The journalist replies by saying that people should not be seen, much less treated, as if they were cattle. More so when they’re just there to pick up a form that can alleviate the anguish they suffer, a paperwork that takes much less time than the one they spend in line.

Also, as is normal, it must be understood that when receiving a form, everyone always has questions. And you doubt. The police officer is not impressed. “I know what I’m doing.” It doesn’t seem so because in the large crowd there’s a widespread lack of respect for the safe distance or the use of masks.

Suddenly a scream is heard: “He’s slipped in! Officer, that man has sneaked in!” says a woman pointing at an old man with a fancy cane who doesn’t even turn around when mentioned. Most people don’t pay attention. A couple of people let him pass and an old acquaintance comments to OnCuba: “Partner, there are habits that take time to disappear. We are in a Havana line, aren’t we?” True: Hialeah is called the City that Progresses, although it is not known toward where. In the line caused by the coronavirus, surely there were those who felt they were in a line in Havana’s Marianao, the one that in other times was also called the City that Progresses.